Interview | George Logan of Hinge & Brackett

📸 BBC

George Logan, best known as Dr Evadne Hinge, one half of comedy double-act Hinge & Brackett, was due to take to the stage of the Cheltenham Playhouse in The Dowager’s Oyster when lockdown was introduced. Hopefully, it will be rescheduled when it’s safe to do so.

📸 Wiktoria Sedkowska

I first met George and his performing partner Patrick Fyffe – Dame Hilda – when they toured to Edinburgh’s King’s Theatre in The Importance of Being Hilda – a brilliant parody of Wilde’s much-loved classic.

I met George again on a trip to France, a travel assignment. He and his partner Louie ran a guest house, Bel Ombrage, in Le Dorat, and we became became good friends. In this interview, he tells me of his early life growing up gay in 1950’s Scotland and the genesis of Dr Evadne Hinge. Enjoy.

📸 Ian Georgeson/TSPL

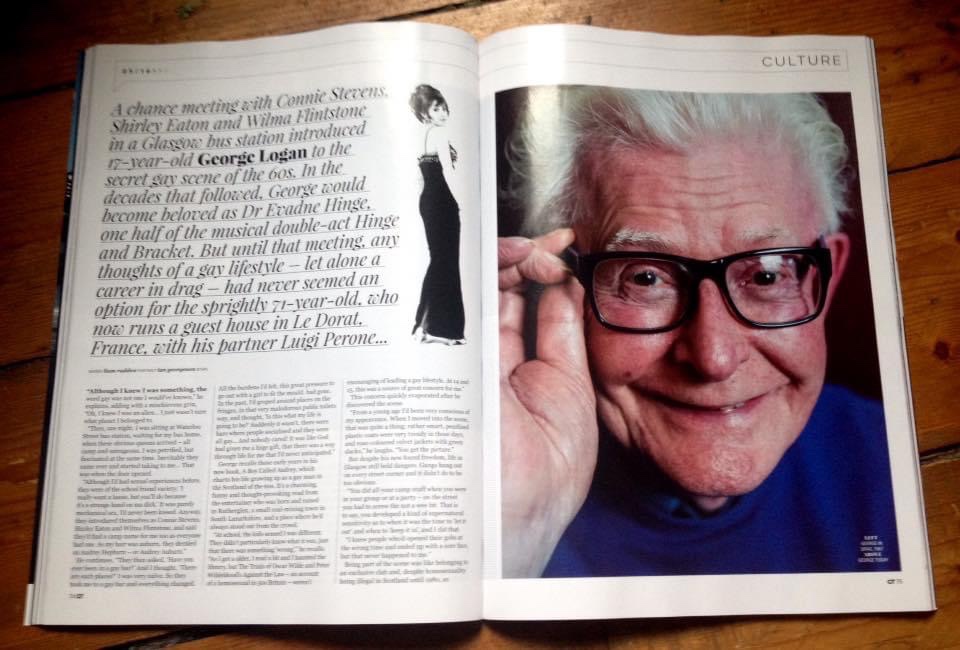

A chance meeting with Connie Stevens, Shirley Eaton and Wilma Flintstone in a Glasgow bus station introduced 17-year-old George Logan to the secret gay scene of the 1960s. In the decades that followed, George would become loved as Dr Evadne Hinge, one half of the musical double-act Hinge and Brackett, but until that moment, any thoughts of a gay lifestyle, let alone a career in drag, had never seemed an option for the sprightly 76-year-old, who now runs a guest house in Le Dorat, France, with his partner Luigi Perone.

“Although I knew I was something, the word gay was not one I would have known,” he explains, adding with a mischievous grin, “Oh, I knew I was an alien… I just wasn’t sure what planet I belonged to.

“Then, one night, I was sitting at Waterloo Street bus station, waiting for my bus home, when these obvious queens arrived, all camp and outrageous. I was petrified but fascinated at the same time. Inevitably they came over and started taking to me… that was when the door opened.

“Although I’d had sexual experiences before, they were of the school friend variety; ‘I really want a lassie but you’ll do because it’s a strange hand on ma dick’. It was purely mechanical sex, I’d never been kissed. Anyway, they introduced themselves as Connie Stevens, Shirley Eaton and Wilma Flintstone and said they’d find a camp name for me too as everyone had one. As my hair was auburn, they decided on Audrey Hepburn or Audrey Auburn.”

He continues, “They then asked, ‘Have you ever been in a gay bar?’ And I thought, ‘There are such places?’ I was very naive. So they took me to a gay bar and everything changed. All the burdens I’d felt, this great pressure to go out with a girl to fit the mould, had gone. In the past I’d groped around places on the fringes, in that very malodorous public toilets way, and thought, ‘Is this what my life is going to be?’ Suddenly it wasn’t, there were bars where people socialised and they were all gay… and nobody cared. It was like God had given me a huge gift, that there was a way through life for me that I’d never anticipated.”

George recalls those early years in his new book, A Boy Called Audrey, which charts his life growing up as a gay man in the Scotland of the 1960s. It’s a charming, funny and thought-provoking read from the entertainer who was born and raised in Rutherglen, a small coal-mining town in South Lanarkshire, and a place where he had always stood out from the crowd.

“At school the kids sensed I was different, they didn’t particularly know what it was, just that there was something ‘wrong’,” he recalls. “As I got a older I read a bit, I haunted the library, but The Trials of Oscar Wilde and Peter Wildeblood’s Against The Law, an account of a Homosexual in 1950s Britain, were not encouraging of leading a gay lifestyle. At 14 and 15, this was the source of great concern for me.”

📸 Líam Rudden Theatre

This concern quickly evaporated after he discovered the scene. “From a young age I’d been very conscious of my appearance. When I moved into the scene, that was quite a thing; rather smart, pearlised plastic coats were very trendy in those days and rose coloured velvet jackets with green slacks, you get the picture,” he laughs.

Despite his new found freedom, life in Glasgow still held dangers. Gangs hung out on every street corner and it didn’t do to be too obvious.”You did all your camp stuff when you were in your group or at a party, on the street you had to screw the nut a wee bit, that is to say, you developed a kind of supernatural sensitivity as to when it was the time to ‘let it out’ and when to ‘keep it in,’ and I did that. I knew people who had opened their gobs at the wrong time and ended up with a sore face, but that never happened to me.”

Being part of the scene was like belonging to an exclusive club and, despite homosexuality being illegal in Scotland until 1980, as opposed to 1967 in England and Wales, George recalls the police tended to approach the law with a very light touch. “Although I’d heard of people in the 1950s who had got into trouble for being in a gay relationship, I never knew of any in my time. That they didn’t pursue people in relationships was something that came to my attention when I got into trouble with the law – my father was told by a police officer that the higher-ups had said not to pursue people who had private gay relationships, just to keep an eye out for gatherings.”

📸 Líam Rudden Theatre

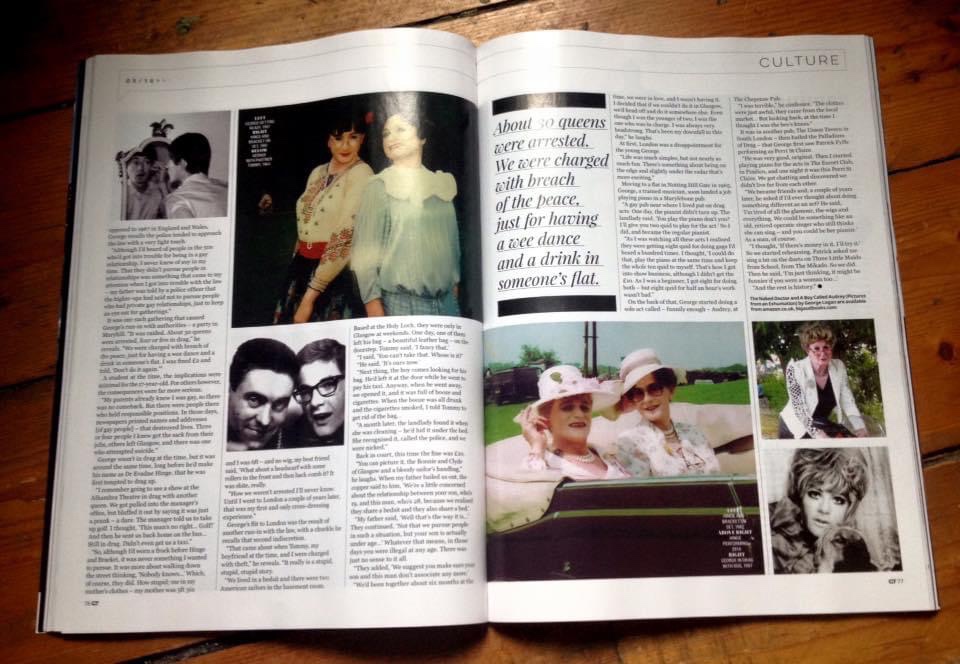

It was one such gathering that caused George’s run in with authorities – a party in Maryhill. “It was raided. About 30 queens were arrested, four or five in drag,” he reveals. “We were charged with breach of the peace, just for having a wee dance and a drink in someone’s flat. I was fined £2 and told, ‘Don’t do it again’.”

A student at the time, the implications were minimal for the 17-year-old , for others however, the consequences were far more serious. “My parents already knew I was gay so there was no comeback but there were people there who held responsible positions. In those days, newspapers printed everybody’s names and addresses – that destroyed lives. Three or four people I knew got the sack from their jobs, others left Glasgow, and there was one attempted suicide.”

George wasn’t in drag at the time, but it was around the same time, long before he’d make his name as Dr Evadne Hinge, that he was first tempted to drag up.

“I remember going to see a show at the Alhambra Theatre in drag with another queen. We got pulled into the manager’s office but bluffed it out by saying it was just a prank, a dare. The manager told us to take up golf. I thought, ‘This man’s no right… Golf!’ And then he sent us back home on the bus… still in drag. Didn’t even get us a taxi.

“So, although I’d worn a frock before Hinge and Brackett, it was never something I wanted to pursue. It was more about walking down the street thinking, ‘Nobody knows…’ Which, of course, they did. How stupid; me in my mother’s clothes – my mother was 5ft 3in and I was 6ft – and no wig; my best friend said, ‘What about a headscarf with some rollers in the front and then back comb it? It was shite really. How we weren’t arrested I’ll never know. Until I went to London a couple of years later, that was my first and only cross-dressing experience.”

George’s flit to London was the result of another run in with the law, with a chuckle he recalls that second indiscretion.

📸 Ian Georgeson/TSPL

“That came about when Tommy, my boyfriend at the time, and I were charged with theft,” he reveals. “It really is a stupid, stupid, stupid story.

“We lived in a bedsit and there were two American sailors in the basement room. Based at the Holy Loch they were only in Glasgow at weekends. One day, one of them left his bag, a beautiful leather bag, on the doorstep.

“Tommy said, ‘I fancy that.’ I said, ‘You can’t take that. Whose is it?’ He said, ‘It’s ours now.’ Next thing, the boy comes looking for his bag. He’d left it at the door while he went to pay his taxi. Anyway, when he went away, we opened it… it was full of booze and cigarettes. When the booze was all drunk and the cigarettes smoked, I told Tommy to get rid of the bag… A month later, the landlady found it when she was cleaning, he’d hid it under the bed. She recognised it, called the police, and we were nicked. Back in court, this time the fine was £10.

“You can picture it, the Bonnie and Clyde of Glasgow and a bloody sailor’s handbag,” he laughs. “When my father bailed us out, the copper said to him, ‘We are a little concerned about the relationship between your son, who is 19, and this man who is 28, because we realised they share a bedsit and they also share a bed.’

“My father said, ‘Well that’s the way it is…’ The policeman continued, ‘Not that we pursue people in such a situation, but your son is actually under age…’ Whatever that means, in those days you were illegal at any age. There was just no sense to it all.

“They added, ‘We suggest you make sure your son and this man don’t associate any more.’ We’d been together about six months at the time, we were in love, and and I wasn’t having it and decided that if we couldn’t do it in Glasgow we’d head off and do it somewhere else. Even though I was the younger of two, I was the one who was in charge. I was always very headstrong. That’s been my downfall to this day,” he laughs.

At first, London was a disappointment for the young George. “Life was much simpler but not nearly as much fun. There’s something about being on the edge and slightly under the radar that is more exciting.”

Moving to a flat in Nottinghill Gate in 1965, George, a trained musician soon landed a job playing piano in a Marylebone pub.

“A gay pub near where I lived put on drag acts. One day, the pianist didn’t turn up. The landlady said, ‘You play the piano don’t you? I’ll give you two quid to play for the act?’ So I did, and became the regular pianist. “

“As I was watching all these acts I realised they were getting eight quid for doing gags I’d heard a hundred times. I thought, ‘I could do that and play the piano at the same time and keep the whole 10 quid to myself. That’s how I got into show business, although I didn’t get the 10 quid. As I was a beginner I got eight for doing both – but eight quid for half an hours work wasn’t bad.”

📸 George Logan

On the back of that, George started doing a solo act, called, funnily enough, Audrey, at The Chepstow Pub. “I was terrible,” he confesses. “The clothes were just awful, they came from the local market. I thought I was the bees knees… but looking back.”

It was in another pub, The Union Tavern in South London, then hailed the Palladium of Drag, that George first saw Patrick Fyffe, performing as Perri St Claire.

“He was very good, original. Then I started playing piano for the acts in The Escort Club, Pimlico, and one night it was this Perri St Claire. We got chatting and discovered we didn’t live far from each other.

📸 BBC

“We became friends and a couple of years later he asked if I’d ever thought about doing something different as an act? He said, ‘I’m tired of all the glamour, the wigs and everything. We could be something like an old retired operatic singer who still thinks she can sing and you could be her pianist’. As a man, of course. I thought, ‘If there is money in it, I’ll try it.’

“So we started rehearsing. Patrick asked me to sing a bit on the duets on Three Little Maids From School, from The Mikado. So I did. Then he said, ‘I’m just thinking, it might be funnier if you were a woman too…’ “And the rest is history.”

Dr Evadne Hinge and Dame Hilda Brackett were born.

A Boy Called Audrey (Pictures from an Exhumation) by George Logan is available in paperback, £12.99, from www.amazon.co.uk